Maintenance masterclass

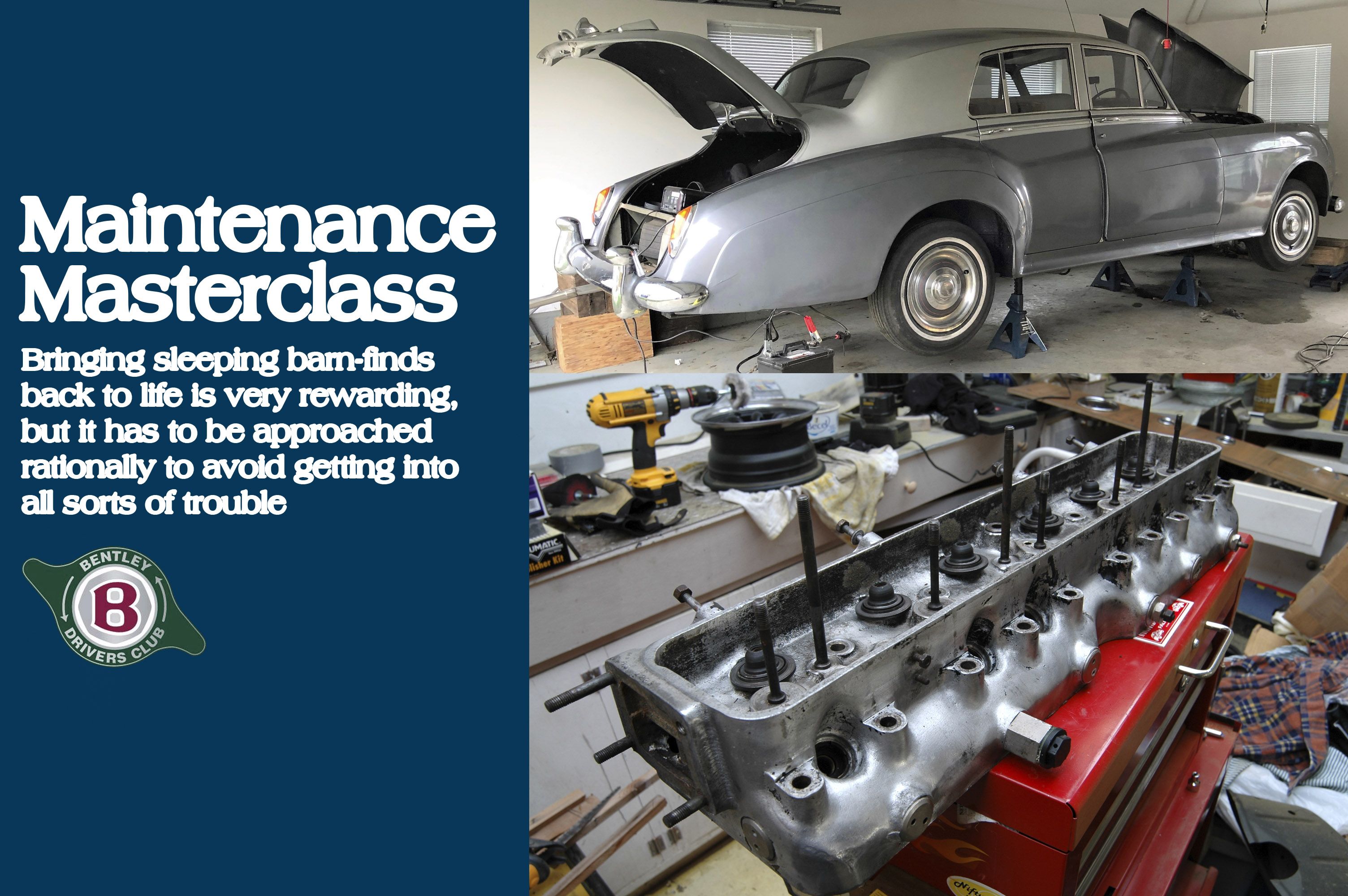

Bringing sleeping barn-finds back to life is very rewarding, but it has to be approached rationally to avoid getting into all sorts of trouble, warns Iain Ayre. Images: Courtesy of Author

Barn-finds can often be viewed with a romantic eye, the prospect of bringing back to life a car that has lain undiscovered for ages. But, in your excitement, you need to ensure that the resurrection of the vehicle is carried out in a careful and measured fashion.

For instance, you don’t just throw some fuel in and jump-start the engine, or you can break piston rings and bend stuck valves (I’ve seen that happen). Even if the engine in question didn’t need a rebuild before, it probably does now.

Having said that, psychologically it’s not a bad idea to prepare and fire up the engine quite early in the rehabilitation process: it reawakens the car and will fire up your enthusiasm too.

There is also the primary barn-find question that needs an answer: what was the probably major problem that caused the car to be abandoned in a barn in the first place?

Step One

Take out the plugs and spray lots of releasing fluid into the cylinders in case the piston rings have rusted or stuck to the bores. If that’s the case they will likely snap, but you were probably in for a rebore and new pistons anyway.

In my 1957 S1’s case, the compressions had been recently checked and were all within 10 per cent of 120psi, which is fine for a low-compression engine like this one. New rings had previously been fitted and the bores were honed, and the engine had been run fairly regularly after that. There was no smoke, which was great news.

Turn over the engine by hand for several revolutions, with a socket and probably a two-foot lever; if you need to add an encouraging stick to shift it, again you’re probably looking at a rebore, although it might just be kak and stiction if you’re lucky (those are technical Bentley engineering terms, by the way!). Start off by moving the crankshaft and pistons back and forth just a few degrees before progressing to full revolutions. The more releasing fluid, lubrication and patience you can bring to bear at this critical stage of the process, the higher the likelihood of success.

Step Two

Change the oil and filter. I once took a filter off a Rolls-Royce engine and it was packed with solid dry filth: it looked like an evil-chemical-barrel Harrison Ford film prop. The oil in the sump will give you a guide to the engine’s past: if it’s low, black and runny that means poor maintenance.

Don’t use flushing oil – it can flush detritus into the bearings. Another local Bentley chum is ruefully listening to what is probably the tapping of a damaged small-end bearing in his Mk VI engine, having done exactly that.

Step Three

Leave the ignition disconnected and turn over the engine on the starter motor to get oil pressure. We need to know what the expected cold oil pressure should be. Electric gauges are okayish, but a physical capillary tube oil pressure gauge is best.

Step Four

Find a fire extinguisher, as we’re about to add petrol and ignition to the experiment – spectacular fuel incontinence combined with sparks is a possibility.

Step Five

See if the engine fires. Connect the ignition and attach one of the plugs to its lead, then turn over the engine with the spark plug body touching something steel to see if there is a spark at the plugs: a fat blue spark is great, a small yellow one will do. Take off the air filter, tip a little fuel into the carb(s), stand back and try the starter. If the engine tries to run, excellent – we’re nearly in business.

Use very fresh fuel. Modern fuels morph into varnish and vapour very quickly, and if the tank has had any modernish fuel left in it for any time, that will have turned nasty and will need to be cleaned out.

Step Six

This step concerns the cooling system. If the radiator is empty and you’re just going to see if the engine works, you can run it very briefly with no coolant as long as it has oil.

Empty the radiator and heater, and back-flush it with a garden hose. Consider distilled water or specialised coolant for permanent use, depending on where you live: the water in Glasgow is pure and filtered through mountains, while the water in London is full of limestone calcium and has been drunk and recycled seven times or some such. If you wouldn’t put it in your teapot, don’t put it in your engine.

Run the engine up to temperature, check that the heater matrix is getting hot and not leaking, and then check the whole surface of the radiator with a laser temperature gun. It should be cooler at the bottom hose than the top hose if the rad is working well, but if it’s stone cold at the bottom, that can mean it’s full of kak and needs a major chemical cleanout at a rad specialist, a recore or replacement.

Step Seven

This step is all about rubber and gaskets. After about seven years, modern synthetic rubber goes hard – this applies to every piece of rubber in the car, including the tyres which are also subject to UV deterioration in sunlight.

The brake hoses are also rubber and could be 30 years old as well. No question, just buy new ones. The Bentley has an early dual brake system with two sets of wheel cylinders at the front, but it’s not worth taking any risks with brakes.

The old rubber fuel hoses also pose something of a risk if they split, so out they come as well. The main cooling and heater hoses are worth changing too, even if they still look and feel soft enough. The old ones can go in a box in the boot to act as spares on long trips.

Modern fuel, rich with unpleasant chemicals, eats old fuel system gaskets and seals. The historically rebuilt carbs on the Bentley may still have new/old gaskets and seals, although the metal parts will be fine. Another rebuild with brand new soft materials is wise.

On the early V8, used in the prototype of Iain’s S1 convertible conversion, the compressions were 115-120lbs on the right bank and randomly 70s and 90s on the left. That means a failed head gasket and potentially water in the wrong place

The 30-years-unused engine in Iain’s Silver Wraith turned over freely but he checked the oil filter before starting it up. This is what came out: the engine would have been wrecked very quickly if it had been started

On straight sixes, all sorts of kak can come from the cooling system and be deposited at the back of the water jacket where the coolant flow is slow. Clearing it out avoids a possible rear piston seizure on such engines

The floats in my S1 carbs had cracked and sunk. I rebuilt the carbs with new floats, gaskets and seals to cope with modern fuels

If the laser temperature gauge focused on the radiator surface says the coolant is steadily losing heat as it passes through the matrix, all is well

Budget for changing all the rubber seals and hoses in the brake system. Also inspect the condition of the brake cylinders

This looks like a good winter tyre with lots of extra sipes, but instead they’re cracks and this fossilised tyre would probably burst if driven at speed

Upmarket interiors attacked by damp can pose substantial problems. The leather surface here doesn’t look bad, but the woodwork might need new veneer or complete replacement, and the headlining is getting nasty

Thank you to the Bentley Drivers Club (BDC) for giving us kind permission to use this article on our website.

Become a member of the Bentley Driver Club today, visit www.bdcl.org/membership