Maintenance Masterclass

This piece was originally published in The Review and appears here as part of our Bentley Drivers Club collaboration .

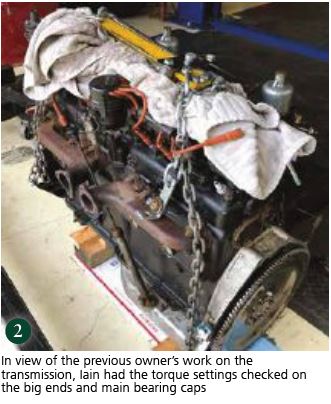

Iain Ayre shares the grief of Hydramatic dramatics and automatic transmission trauma as he overhauls his S1. Images: Courtesy of Author

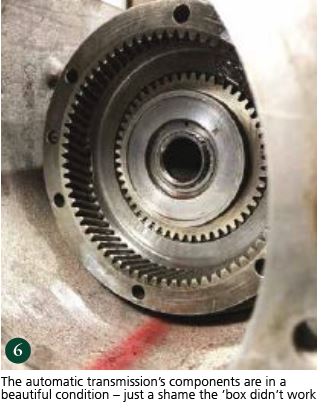

The General Motors/Rolls- Royce Hydramatic gearbox fitted to many Bentleys from 1952 to 1967 is a well-established and very solid piece of kit, an American drag racers’ favourite. Its downsides are slightly lumpy gearchanges if maladjusted, and a tendency to sulk if unused, but the cost/benefit analysis still comes out with its thumbs up.

The Hydramatic was first used in Oldsmobiles in 1939. It was developed during the 1930s, when the whole idea of automatic gearchanging was new, so conceptually it’s different from most autobox technology in using a fluid coupling rather than a torque convertor. There’s also no park position – it uses a pawl in reverse gear to provide a parking lockup. The gearbox was complex and expensive to make, but is slightly more fuel-efficient than the alternatives.

The earlier and smaller version of the ’box found behind the sixcylinder Bentley engines in R Types and S1s can also give solid service, but the consequences of neglect can be expensive. Both of these transmissions need to be used in order to remain healthy: it seems that otherwise the fluid drains to the bottom and the complex internal components start rusting.

If you’re buying a rarely used six-cylinder Bentley, make sure the transmission is working well; if not, budget for a rebuild. A lumpy change into third gear can often be improved by adjusting the internal bands from outside the ’box. The later and larger Hydramatic transmission on V8s seems to be less problematic in general, but the earlier transmission on my 1957 S1 descended into nightmare.

My Cunning Plan three years ago was to buy the car, flat-deck it home, bleed the brakes, take it for a drive, then cut the roof off and turn it into the prototype for a series of Ayrspeed two-door convertible conversions. Two years and six months later, taking it for a drive remains a distant rose-tinted dream. The engine runs well, no problem there. The elegant one-finger electric gear selector seemed to select as suggested – but forward motion came there none. Backwards with some revs got the hint of a feeble lurch, although that was all.

Usually, a lack of drive with an automatic transmission means low fluid. Okay, the previous owner said he had replaced it, but let’s check: there’s a dipstick under the carpet. Empty. Either he forgot to fill it up again or it all seeped out. I had been trying to operate the transmission bone-dry. That, as they say in medical circles, is contra-indicated. Automatic transmissions are operated by small oily fairies using magic, well outside my mechanical comfort zone. I know vaguely how transmissions work, but this one has a fluid coupling rather than a torque converter. I don’t know why a fluid coupling is not a torque convertor, so it was wiser to find greasy magicians to overhaul the ’box.

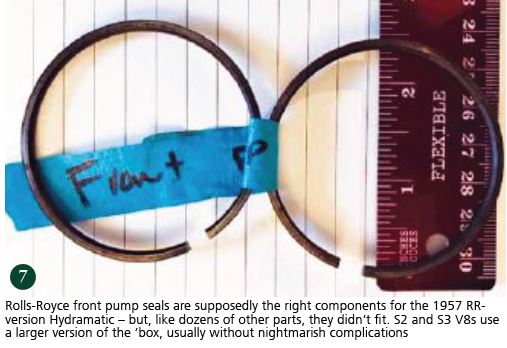

The first transmission shop said it wasn’t a Hydramatic gearbox. Bentley Motors would beg to differ. Given that scary level of expertise, I retrieved the car and squeezed it into the queue of a local restoration shop: I would source the parts myself to control the cost. There are some Rolls-Roycespecific internal parts, and the mechanical brake servo is not found on US Hydramatics, so I bought an overhaul kit specifically for the Rolls/Bentley version of the ’box. The bill for stripping and de-rusting the transmission and removing the brakes came to $10,000 (£6,000) even with a discount: 114 hours. Decades of disuse had resulted in major corrosion inside the gearbox, and all the steel valves that should move under the pressure of a pinky had to be delicately drifted out of their aluminium housings before being de-rusted.

The early Hydramatics have a few obscure parts that differ from later ones, so there was more chasing down seals and springs in the US and UK. But many parts still didn’t fit properly. Possibly my car had been bodged with bits of scrapyard Oldsmobile transmission: who can tell? After another monster invoice, the tranny was finally back in the car. It was bad. It didn’t select the lower gears properly and it vibrated, but I gave it a chance to settle down and drove the seven miles home: those seven miles are still the furthest I’ve driven the car. For one sublime mile at 30mph under low throttle on a country road in top gear, I got a hint of the serenity and smoothness of which an S1 is capable. Then the transmission packed up. There was talk of converting to a T5 manual gearbox: the S1 languished at the resto shop as discussion muttered on.

The attempt to test a second transmission rebuild lasted for 30 feet before a freshly rebuilt machinebronze- lined brake master cylinder stuck solid. Another separate and lengthy nightmare, involving components being posted hither and thither, metals disobeying the laws of physics, patience strained beyond the limit, and possibly the involvement of actual evil spirits: an exorcism might be wise. The new transmission goes through all its gears, but engagement and disengagement is lumpy. Could be throttle rod adjustment? Possibly band adjustment? That is where we are now, two years, six months and counting…